Who Cares About Gorillas?

Ecoflix Blog for World Gorilla Day 2024

Ian Redmond

Happy World Gorilla Day!

First celebrated in 2017 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Karisoke Research Centre, founded by Dian Fossey on September 24th, 1967, World Gorilla Day has grown into a global phenomenon. Since Dian’s murder in 1985, many people have risen to the challenge of protecting what she used to refer to as ‘the greatest of the great apes’, so I thought this blog would be a good opportunity to raise the profile of some of the unsung heroes of gorilla conservation.

Just before World Gorilla Day this year I travelled around Rwanda and eastern Democratic Republic of Congo with the French author, Yasmina Kramer, who is researching her next book by seeing first hand the lives led by rangers, trackers, researchers, vets and others in the multi-national community of conservationists in the Great Lakes region of Africa.

We had arranged to meet at the Hotel Muhabura, where Dian used to stay when she came down from the mountains. The owners, two Rwandan sisters Gaudentia and Theresa, gave me a wonderful welcome as I cycled in from the bus station; they remember Dian warmly and have named her favourite room The Dian Fossey Room – where Yasmina was busy typing when I arrived, just as Dian would have been – the tappety, tap, tap, zzzz-ting of her Olivetti portable typewriter was part of the soundscape that surrounded Dian wherever she went! I remember first staying in the Hotel Muhabura in 1977 when working as Dian’s Research Assistant; she had been invited to give a public lecture in Ruhengeri (the town closest to Volcanoes National Park, now known as Musanze), something she did every year to share the results of her work with the local chamber of commerce and officials. She spoke in a mix of English, French, Kiswahili and Kinyarwanda which must have perplexed the audience but I recall they were captivated by her enthusiasm and the film and photos of the gorillas. Much has changed in the intervening years but despite the many new hotels and luxury lodges, the Muhabura remains my favourite place to catch up with old friends and talk gorilla! One evening the Chief Warden on Volcanoes National Park, Prosper Uwingeli, joined us for a catch-up and Yasmina learned of the plans to restore some 37km2 of the park land lost to agriculture in the early 1970s. How extraordinary that in one of the most densely populated countries in Africa, the government has taken the bold decision to make more room for the growing population of mountain gorillas while simultaneously creating thousands of jobs and resettling families in new purpose-built accommodation.

Retraining former poachers is the goal of the Iby’iwacu Cultural Village, founded by Edwin Sabuhoro, a former ranger who realised that many members of his community turned to poaching out of poverty and set about providing better alternatives. You can read his amazing story here. Yasmina learned about how communities had relied on the forest for food, building materials and medicinal herbs – all resources lost to them when the Volcanoes National Park was founded (originally part of Africa’s first National Park, created in 1925 by King Albert of Belgium). She met some of the reformed poachers, one of whom, and elderly chap named Ezekiel Kaziboneye, had worked as a porter for Dian Fossey in the early days and recounted tales of building the cabins at 10,000ft/3,000m in the saddle between Mounts Karisimbi and Visoke (hence the name Karisoke, which Dian invented).

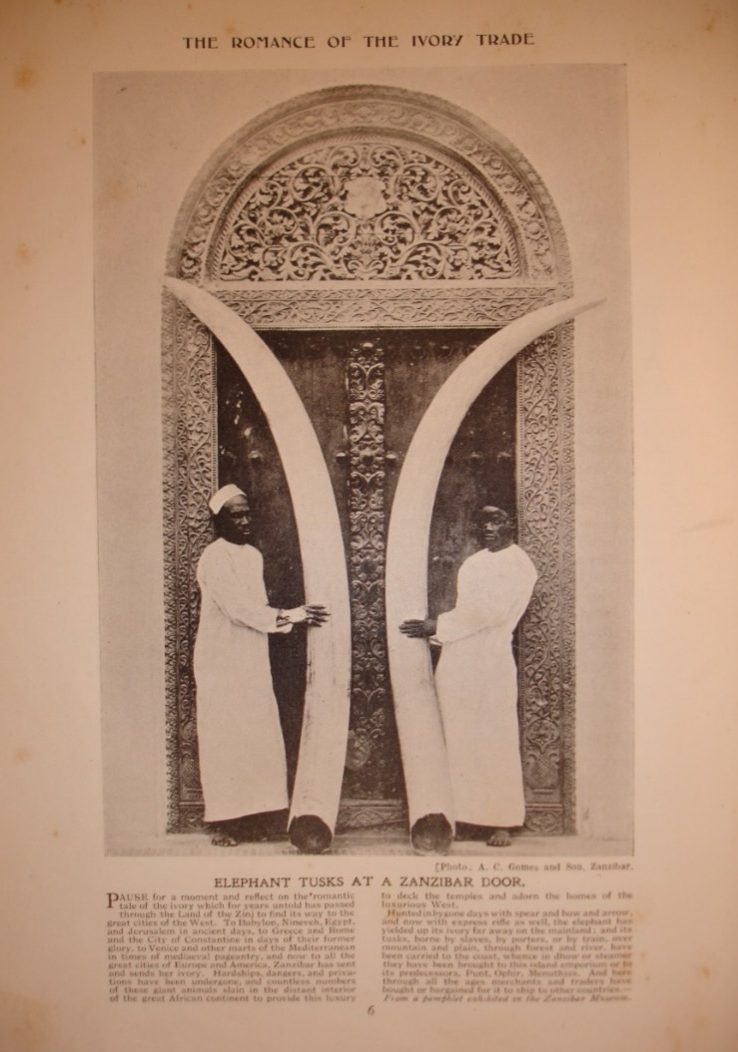

Ian Redmond, Emmanuel Harerimana and Ezekiel Kaziboneye, three generations of gorilla workers.

We were greatly assisted by Emmanuel Harerimana, a gorilla guide, former poacher and founder of Muhisimbi, Voice of Youth in Conservation, which now runs a wonderful centre for teenage mothers and their children. Emmanuel was mentored by Edwin Sabuhoro and is now mentoring dozens of young Rwandans, passing on his passion for conservation.

A highlight of our time in Rwanda was climbing up to the site of the old Karisoke cabins, now completely demolished, to pay our respects at Dian’s grave. Yasmina told me she was first captivated by Dian’s story when she saw the movie, Gorillas in the Mist as a girl. Now, decades later she was greatly moved by visiting the place where it all happened and spending some quiet time in the beautiful glade where Dian and several gorilla poacher victims are buried.

On the way down, walking quietly along the Porters’ Trail, where twice a week supplies and post were carried up the side of the mountain on the heads of a long line of local men – all of whom depended on this work to supplement their subsistence farming – we encountered a group of gorillas who had just crossed the trail. It was not a formal gorilla visit, just a wonderful bit of luck that gave Yasmina her first glimpse of a blackback, feeding quietly in the lush green vegetation as bees buzzed in the sunshine. Magical!

The next day we caught the bus south to Cyangugu, around countless hairpin bends with beautiful views across Lake Kivu, to cross the border into the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). There we were met by Eddy Kahekwa, a rising young conservationist, son of one of my oldest friends John Kahekwa, founder of the multi-award-winning Pole Pole Foundation (PoPoF), which has built a school and now an agricultural college and Spirulina farm to improve the quality of life of people living around the gorilla habitat. John often cites a poacher who explained why he ignored the advice of conservationists by saying, “empty stomachs have no ears!” Community conservation has been shown to work and PoPoF has received awards from Whitley Fund for Nature, Tusk and most recently the Earthshot Prize!

John was a gorilla guide in Kahuzi-Biega National Park when we first met in 1983. Many visitors to gorillas in Rwanda and Uganda do not know that it was here in Congo that habituated gorilla tourism began, thanks to the work of Adrien Deschryver, a Belgian hunter-turned-conservationist who established and was the first warden of Kahuzi-Biega. He had a very different approach to gorilla habituation than Dian Fossey, preferring to face the charging silverback speaking softly rather than using gorilla contentment vocalisations and non-threatening body language as practiced by Dian and her students. In the 1980s many tourists visited both sub-species of gorilla but sadly the years of civil war and insecurity mean that few tourists venture into the DRC today. This is such a shame because the warm welcome and gorilla tracking experience is equal to that which you might find in Rwanda and Uganda, and is significantly cheaper. By arrangement with the park, it is easy to get a visa on the border and visit the gorillas, thereby helping to fund the park and create employment opportunities in the surrounding area.

The park is now co-managed by the Congo Conservation Institute (ICCN) and the Wildlife Conservation Society, and by chance Yasmina and I arrived just as a new cohort of eco-guards were graduating and being presented with their certificate. The Warden, Dr Arthur Kalonji, a veterinarian, gave a rousing speech about the new graduates being the future of conservation in the park and their pride in becoming eco-guards was self-evident.

Graduation Day, PNKB.

The challenges they face were made clear afterwards in a briefing by Erik Saudan of WCS, who had helped train them. With the latest GIS mapping, he showed how serious the deforestation for illegal agriculture and charcoal production was in parts of the park too insecure to patrol regularly.

4,000 bags per week of Charcoal from PNKB go to market in Bukavu, DRC.

The most westerly part of the park, for example, requires a six-day hike to get to the boundary to then begin to patrol! Most serious is the damage to the corridor that links the montane sector with the much larger lowland sector – here, influential people have built homes and roads to access them, despite the park being a UNESCO World Heritage Site, considered to be of outstanding universal value to the world. The Pole Pole Foundation has the task of restoring the forest here – essential to maintain gene flow in animal populations in both sectors – but this will not be easy given the local politics. Most important is keeping the corridor open for elephants to re-populate the montane sector, where they were all killed during the civil war. One of the saddest sights is the pile of elephant skulls at the park headquarters – remains of the mega-gardeners of the forest whose loss has led to a deterioration in the quality of gorilla habitat.

Lambert Cirimwami laments the killing of elephants by poachers.

Before leaving DRC, I called in to see Carlos Schuler, who with his wife Christine Schuler-Deschryver, managed the German Technical Aid (GTZ) support for Kahuzi-Biega during eight years of civil war, refugee crisis and turmoil. He tells his remarkable story in Vivre et Survivre en RD Congo (originally in German but not yet in English – publishers please take note!). At a time when almost all expatriate left the DRC, Carlos worked with his ICCN colleagues to keep the park going, organised food distribution for thousands of local people and with the help of the Born Free Foundation, develop the infrastructure of the park HQ.

It is no exaggeration to say that had they not been there during the war after the Rwandan genocide, the gorillas of the highland sector would likely have gone the same way as the elephants! Carlos is also a talented photographer, as the amazing images in his book attest.

He and Christine (daughter of Deschryver, the park’s founder) have now created the City of Joy, helping women who have been raped build new lives – an inspirational project that was the subject of a recent documentary on Netflix, – search for City of Joy.

As I pedalled back over the border into Rwanda and up the looong, steep hill (that was such fun to wizz down), Yasmina took the ferry across Lake Kivu to Goma to meet Henry Cirhuza, another unsung hero who has for many years managed the DRC projects of The Gorilla Organization (now an Ecoflix partner NGO (https://www.ecoflix.com/ngo/the-gorilla-organization/), supporting community conservation of gorillas in one of the most difficult and unstable parts of the world.

All in all, I guess my conclusion for this World Gorilla Day is that there are so many people devoting their lives to help gorillas and the communities around their habitat that despite all the bad news and population declines in almost all great apes, there is hope!

Check out the documentaries collated for World Gorilla Day on Ecoflix and please support the NGOs working to protect gorillas across the ten African countries where they live.

In memorium: On my return to the UK, I received the sad news that Dr Antoine ‘Tony’ Mudakikwa, a Rwandan vet and one of the key people I had hoped to introduce to Yasmina, is no longer with us. One of the original Gorilla Doctors, Tony was a charismatic and courageous conservationist who pioneered methods of treating mountain gorillas in the difficult conditions of their natural habitat, thereby saving many lives. He represented Rwanda at many UN meetings such as CITES and will be missed by his many friends and colleagues. My condolences to his family. For more details of his scientific work, see https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Antoine-Mudakikwa